Dambisa Moyo argues that aid (development aid) is the cause of Africa’s underdevelopment. This argument hardly holds water.

Correlating Africa’s underdevelopment to aid betrays a misunderstanding of the malignant nature of poverty -not even to mention that correlation doesn’t necessarily explain causation. According to her,“the answer to Africa’s economic underdevelopment has its roots in aid.” (P.6)

Thus Africa’s underdevelopment is not caused by;

Rampant poverty?

Lack of Infrastructural development?

Absence of Foreign Direct Investment?

HIV aids?

Poor governance?

Tropical Diseases like Malaria?

Famine?

Geographic Impediments?

Lack of access to markets?

Absence of technology?

Structural Adjustments Programs (SAPS)?

Illiteracy?

Poor sanitation which contributes to high mortality rate?

Geopolitics; e.g. Cold War when the West was more concerned in maintaining regimes like Mobutu’s at the expense of economic development in Africa?

None of the above explain Africa’s underdevelopment but aid, according to Moyo. In other words, if we simply stop aid, Africa’s economic development will take off like an eagle?

She does not seem to grasp the multicausal nature of poverty.

On the face of it, I find such an argument weak, but most importantly, it betrays her failure in understanding the root causes of poverty and the malignant dynamics of the poverty trap. Cancelling the debt is one part of the equation. And debt cancellation in and of itself will not bring economic development to the continent.

The other part of the equation requires the following;

1. Rich countries need to make good on their promise to raise development aid to 0.7% of their GNP. This promise was made in Monterrey in 2002. This amount is necessary to start denting poverty not only in Africa but around the world. This amount of aid is critical to have those living in extreme poverty have their feet on the first rung of the ladder of economic development as it will make it possible to target infrastructural deficiencies, combat illiteracy, improve agricultural production by raising crop yield, assault malaria and HIV aids. Such a concerted effort will generate the much-needed economic growth needed to lift people out of poverty.

2. Such commitment ought to be sustainable over a defined period of time. According to Jeffrey Sachs, who did an amazing job studying and understanding the dynamics of poverty, the period ought to be at least 10 years.

3. More accountability for the use of aid as it has been poorly structured and squandered. Both aid donors and aid recipients share responsibility for this. During the Cold War, aid was not a sincere attempt to take on poverty in Africa. Those giving aid had as political calculus maintaining clientelist regime in their camp hence accountability for aid usage was the least of their preoccupation, let alone ending poverty in Africa.

Furthermore, Dambisa Moyo swims into contradictions. She argues, rightly so, that aid has been misused by some regimes in Africa. For example, Mobutu. This is a classic example of aid misused for personal enrichment which ought not to be repeated. But yet, she dives into contraction arguing, the Continent needs “Benevolent Despots” to push for reforms.

How many benevolent despots will the continent need to pull out of poverty? She doesn’t say.

How long is benevolent despotism supposed to reign on the continent? The reader is left to guess.

How do we control for “Benevolence” in a putative despot? She is unresponsive.

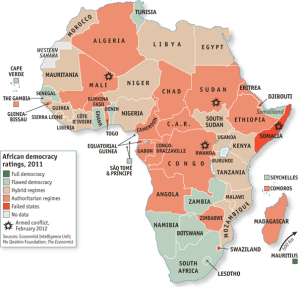

How do we distinguish a “benevolent despot” from Mobutu, Paul Biya, Blaise Compaore, Eyademas in Togo, Bongos in Gabon, ObiangNguema in Equatorial Guinea, the very despots who have squandered aid? She has yet to enlighten us.

I cannot understand how and why she would start by arguing that aid has been mismanaged by the likes of Mobutu and turn around to advocate for benevolent despots in Africa. That strikes me as counter intuitive as Africa needs more accountability not less.

In the final analysis, her book does a great disservice to the cause of ending poverty and underdevelopment in Africa. It fails to run what Jeffrey Sachs calls a “differential diagnostics” to determine and demonstrate the multicausal nature of poverty and its malignant nature.

Worse still, her book is peddling racist stereotypes which explain Africa’s underdevelopment as the result of laziness on the part of Africans.

“Aid engenders laziness on the part of African policymakers.”(P. 66)

Ironically, halfway true her book she had an epiphany arguing; “However worthwhile the goal to reduce and even eliminate aid is, it would not be practical or realistic to see aid immediately drop to zero. Nor, in the interim, might it be desirable.”(P. 76)

Had she started by that realization maybe, just maybe, the book would have added something more in understanding the multicausal nature of poverty and bring forth some meaningful suggestions.

Edwile Vedel M.

Short Response to Edwile’s Quarrel with “Dead Aid” written by Dambisa Moyo

I think it’s disingenuous of my colleague to discredit Moyo’s take on aid and I think to suggest that she doesn’t grasp the poverty on the continent shows a total disregard of her contribution in understanding the relationship between developmental aid and Africa’s underdevelopment. I don’t think Moyo is conclusive that ending aid will lead development, but rather she rightfully says that aid is part of the problem among the many such as leadership and the other problems Edwile points out. I think Edwile has wasted a lot of intellectual capital trying to disprove what some of us already know him included that Africa’s underdevelopment has many moving parts. If Edwile wants answers on the other problems he should find other sources because I think Moyo’s book is specific with aid and not addressing all the problems that Africa is mired in.

Think about it if African leadership was serious enough to utilize its natural resources without the endemic corruption in which millions of dollars are lost annually then sure it is no rocket science that Africa wouldn’t need that much developmental aid. It is evident now that Africa’s endemic corruption is holding Africa hostage developmental wise. Our national budgets are overly reliant on aid as if we cannot harness our own resources. The question Edwile must ask is in spite of all the aid that has been poured into Africa why hasn’t Africa achieved the necessary economic development or traded itself out of perpetual poverty.

For the past 40 years or so African countries have been with the help of aid trying to attain self sustaining national economies, create markets and industries that would generate economic growth and development. In spite of that fact our manufacturing is in limbo we still produce raw materials that we cannot manufacture into final products.

This notion that Africa needs aid in order to develop is misplaced what Africa in my view needs is good leadership that is honest and can manage people’s expectation and ready to offer an ideological orientation that does not undermined Africa’s growth. In a nut shall aid eradication isn’t Africa’s answer to development or reducing poverty, but rather its one of the many tools in the tool kit that can force governments to think creatively and be responsible and accountable to how the national coffers are managed.

To be fair Edwile implicitly raises a question of how Africa has been betrayed by poor leadership on a number of fronts chief among them aid. African people need reliable governments that can deliver on the promise of development, prosperity and self-reliance for the people short of that we will be debating whether Moyo is RIGHT or WRONG on aid. Can African governments work for us and restore hope in our eyes.

Denis Bogere.